Being diligent UX designers, we wanted the users to tell us which area to explore but initially assumed residents would want a microsite on government services or elected officials.

We developed a series of questions with our assumptions in mind. We wanted to get people talking about their relationship with the city and how they felt about it. We inquired on the current city site, asked about government services and local officials, and posed open ended questions about what citizens want to know about the city. We armed ourselves with candy bars and smiles and headed to the Olgilvie Transportation center to conduct interviews.

The city of Chicago is the third largest city in the United States. We had to make sure interviewees were as diverse as the population they represented. African American, Hispanic and Caucasian individuals of both genders were among our interviewees. We made audio recordings to capture all the insights and to allow us to be “present” during the interviews.

This is the part where I tell you that we were wrong.

We assumed government services and local official information would be important to residents, but our interviews contradicted those assumptions.

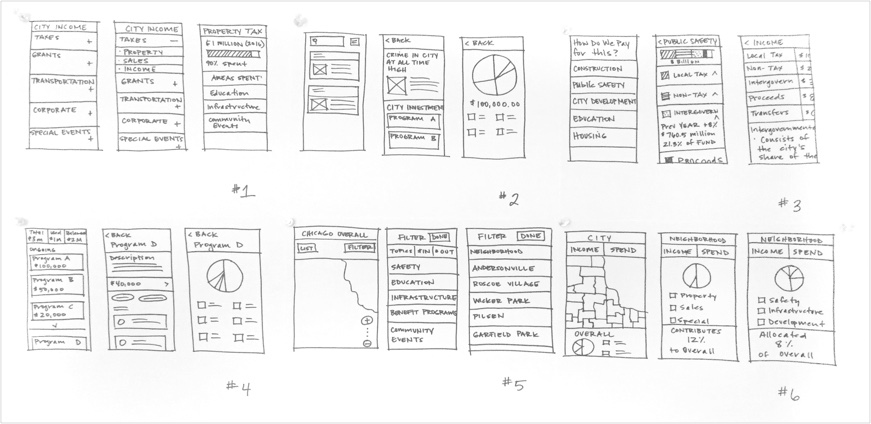

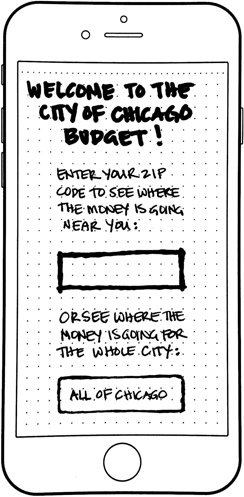

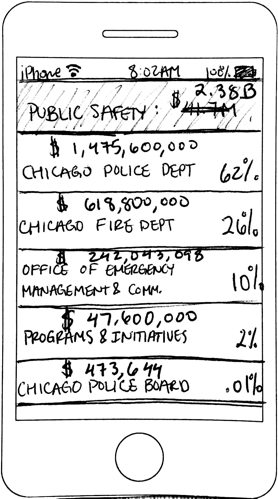

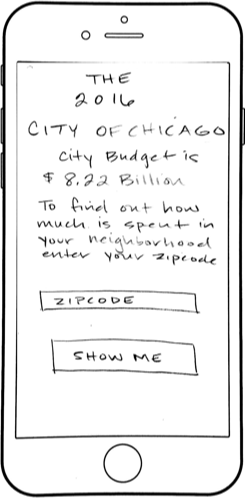

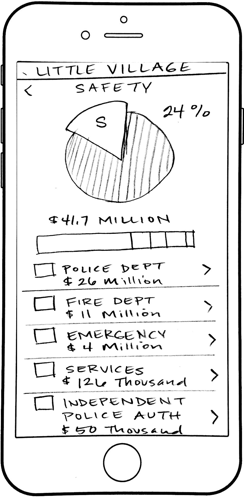

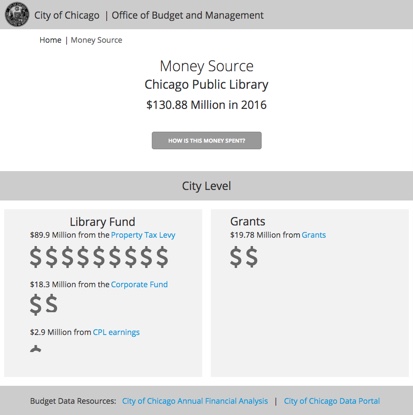

The Individuals we interviewed cared about transparency. They didn’t trust the city and they wanted to keep an eye on it. Was there an area of the city that needed transparency more than any other? Yes, to our surprise, the residents we interviewed wanted budget transparency.

tl;dr:

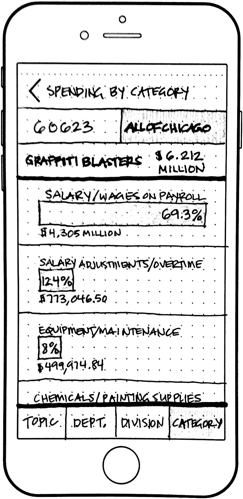

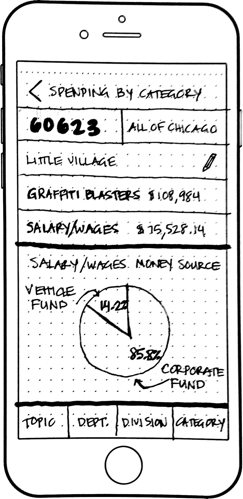

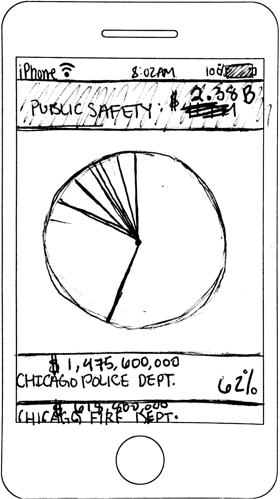

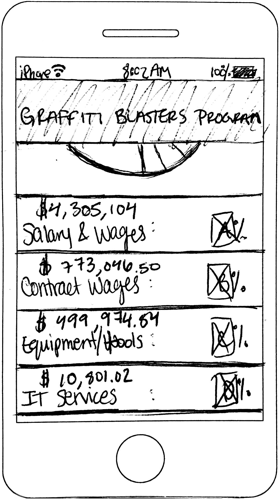

Chicago residents wanted a microsite that increased budget transparency.